In this post I present a closer look into the developments in the Norwegian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the Marginal Productivity of Debt (MPD) from households, non-Financials and municipalities.

Further a brief update on developments in credit/debt growth (for households, non-Financials and municipalities) in Norway. Sovereign debt and debts in the financial sector are not included in this analysis and for a complete analysis ALL DEBTS have to be included. Norway is a small and open economy that is exposed to developments in the global economy (like the price of oil) and its trade relations.

This post is an expansion to my previous post A closer Look into the Drivers of the Norwegian Economy’s recent Growth Success with some updates.

The post also presents a brief look at how recent years developments in the oil price and total petroleum extraction and sales have affected Norwegian GDP, credit/debt growth, the MPD and petroleum related expenditures and what this may portend for the near future.

NOTE: All financial data in this post are in the Giga Norwegian krone (GNOK; Billion NOK) unless otherwise specified. 6 NOK approximates now around 1 US dollar.

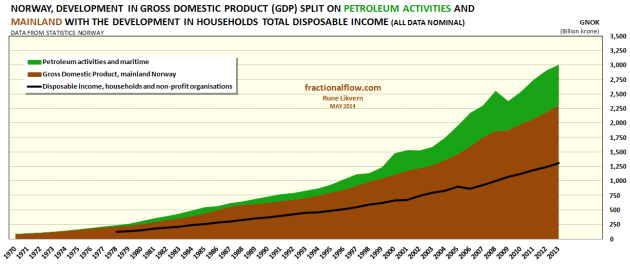

The black line shows the development for total nominal disposable income for Norwegian households.

The chart illustrates how the Norwegian GDP has been on a steady growth trajectory during the recent four decades and how petroleum activities, which started in the late 1960’s, gained in relative importance of GDP developments. The effects of growth in the petroleum activities are documented to spill over into the mainland GDP.

In 2013 around 23% of Norway’s GDP was from petroleum related activities.

The acceleration in the Norwegian GDP from around 2004 have been identified to come from two main sources;

- The growth in the oil price that really took off from around 2004 spilled over to the mainland economy.

- The credit/debt growth from households, non-Financials and municipalities.

This was likely triggered by the growth in the oil price as it revived consumers’ perception of improved outlooks to service more debt as disposable income grew and interest rates started to decline (cheap credit), which again was reinforced from the feedback from rising housing prices and growth in stock indices (equity growth).

As Norwegian petroleum extraction is in general decline and its gross revenues subject to oil price developments, the remaining force to sustain Norwegian GDP growth is to entice the households for continued growth in debt financed consumption.

Continue reading “NORWAY’s PETROLEUM ECONOMY STRUGGLES WITH DECLINING DEBT PRODUCTIVITY”

![Figure 1: The chart above is a composite of two charts. The bottom chart shows the developments for the total central banks’ assets on the balance sheets and the interest rate for Federal Reserve [Fed], European Central Bank [ECB], Bank of England [BoE] and Bank of Japan [BoJ]. Developments in total central banks’ assets in US$ Trillion are shown by the green line and plotted versus the outer right hand scale. Developments in the interest rate (%) are shown by the dark blue line line and plotted versus the inner right hand scale. On top of the chart and with synchronized time axes is overlaid the development in the oil price (US$/Bbl, Brent spot), red line and plotted versus the left hand scale.](https://runelikvern.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/f19b4-fig-1-oil-price-cbs-balance-sheets-and-oil-price.png?w=631&h=344)

![Figure 01: The 6 panel graphic above shows global bank credit aggregates and the most important borrower regions. The chart at upper left shows that global bank credit more than doubled from 2000 to 2013. In the US [upper middle chart] the growth in bank credit slowed from around 2007 (the subprime/housing crisis) and overall credit growth was continued by increased public borrowing for deficit spending. In the Euro area [upper right chart] the total debt levels led to a slowdown in growth of bank credit post 2008 (or the Global Financial Crisis; GFC) and more recently it appears as deleveraging has started [default is one mechanism of deleveraging]. In the Euro area petroleum consumption is now down around 13% since 2008. Asia Pacific [lower left chart] which includes China, continued a strong credit growth and thus carried on the global credit growth. Latin America [lower middle chart] which includes Brazil, continued together with Asia Pacific the strong total global credit growth. Global GDP in 2013 was estimated at above $70 trillion.](https://runelikvern.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/acc6f-fig-01-bis-global-bank-credit.png?w=630&h=541)

You must be logged in to post a comment.